In the autumn of 1995, Miuccia Prada presented a collection of womenswear for the following summer, which combined clashing patterns (checkered oilcloth prints from the 1950s with flashes of faux tweed and floral fabric) with dramatic new colour contrasts (pale brown, Pan Am blue, lurid green, and mauve—all colors that, for PRADA fans, were like a fashion epiphany). The look went down in history as “Ugly Chic.”

With this collection, Prada turned her back on the cool, black elegance of her Italian minimalism, the standard dress code of the art and fashion world in the early 1990s. A fetish object of that avant-garde was the PRADA nylon rucksack made of an artificial parachute silk—a war-tested high-techmaterial that brought functionality into the fashion world. This artificial silk and its very unfeminine processing recalled Futurism and its leading light Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who idolised speed and the desire to attack, launched himself with enthusiasm into the First World War, and outlined a complete renewal of human sensibilities in his MANIFESTO OF FUTURISM (1909).

The Italian Futurists consistently included fashion in their visions. Whereas Marinetti, in theory, vigorously assigned it to military stringency and functionality, the Futurist artist Thayaht (pseudonym of Ernesto Michahelles) saw it embodied in the blue TuTa overall he designed in 1918, reflecting the uniformity of Soviet garb. Other artists in the movement welcomed fashion as an extension of their painterly medium. Fortunato Depero designed waistcoats in graphic and convulsive patterns, as an ironic reference to the dark suits worn by most men in those days. His colleague Giacomo Balla, meanwhile, created shockingly colourful patchwork suits with vector inserts that referenced the Futurist concept of simultaneity, in a bid to get rid of all neutral, pleasing, bland—“humiliating”—colors. Like Marinetti, he also looked to military metaphors, declaring that he wished to colour Italy with Futurist audacity and dress Italians, at last, in joyful and bellicose garb.

Inspired by these approaches, Prada navigated experimentally between the extremes of Futurist stances. As a student of political science, she had joined the Communist Party in the 1970s. While distributing leaflets, she wore YVES SAINT LAURENT suits from her mother’s wardrobe, which, as her husband Patrizio Bertelli recalls, she combined with elements of military uniform. Thus, as a mold-breaking feminist, she also demonstrated against the standard drab look of her fellow party members and stood up for the right to bring fashion into her political identity. This evaluation of fashion as an element of subversion was not new; it had merely been forgotten. As the poet Volt (pseudonym of Vincenzo Fani Ciotto) declared in his FUTURIST MANIFESTO OF WOMEN'S FASHION (1920), fashion had always been more or less futuristic, driven by speed, innovation, and creative courage, exactly like art. As he put it, a brilliantly designed dress, worn with confidence, exuded the same aura as a fresco by Michelangelo or a Madonna by Titian. PRADA's nylon backpacks and oilcloth coats were anticipated by Ciotto’s manifesto, which spoke of a hundred new revolutionary materials taking the public arena by storm. He even predicted the London punks with rats on their shoulders when he recommended that designers should use living animals—as well as rubber, fish skin, paper, glass, ceramics, and cascading plants—in their creations.

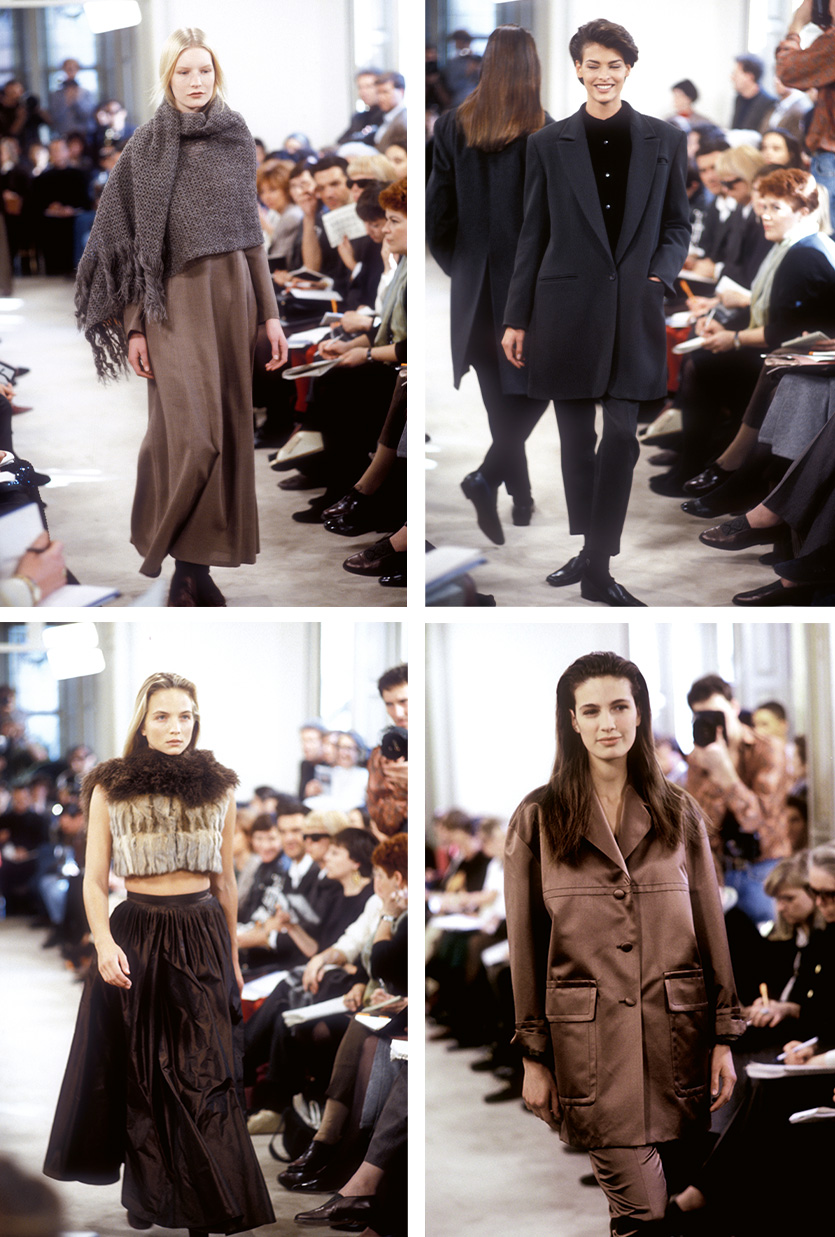

Miuccia Prada’s shift from minimalism to a strong fashion statement, from uniformity to patterns and bold colors, may be interpreted as both a biographical and cultural self-affirmation. The robust fabrics, sharp tailoring, epaulettes, stiff collars, and metallic belt buckles of her early 1990s designs would have fitted right into Greta Garbo’s wardrobe in NINOTSCHKA (1939), the Ernst Lubitsch film in which she portrays a Soviet commissar operating in Paris. In the early 1990s, Prada ran ascetic campaigns with lots of white space and small documentary-style images accompanied by a prominent PRADA logo recalling the masthead of the Moscow daily newspaper PRAVDA.

It is worth dwelling for a moment on this PRADA logo. The enigma of the all-caps wordmark is created by the way the right leg of each letter A pushes so forcefully to the left that the slender left leg is barely able to counter it. This pressure is also exerted on the R, which appears to be put on the defensive, almost to the point of turning back on itself—which would effectively transform it into the Cyrillic letter Я (which, incidentally, means “I”: myself). The unbroken right side of the A, physiologically reminiscent of a PRADA stiletto shoe, seems to be about to pirouette. This virtual turnaround plays not only on the self-absorbedness inherent to fashion consumption, but also on the quotation-laden and reflection-saturated elasticity of PRADA’s fashion, which captivated the hearts of the western intelligentsia.

Intellectualism became Prada'’s hallmark. Ugly Chic made sense only against the backdrop of artistic expression that, since Hegel’s rebuttal of the beauty of art, could no longer be described as les beaux arts, giving preference instead to the interesting, the fragmentary, and the ugly. Jean Paul Gaultier, Pierre Cardin, and the punks had already gone down that path, but whereas the French designers cultivated the stridently burlesque and the punks went for the aggressive, Prada moved in the middle ground between the ugly and the beautiful, the taboo and the norm. She questioned habitual ways of seeing, without insulting them. Her focus was on the interesting, which posed a conundrum to connoisseurs.

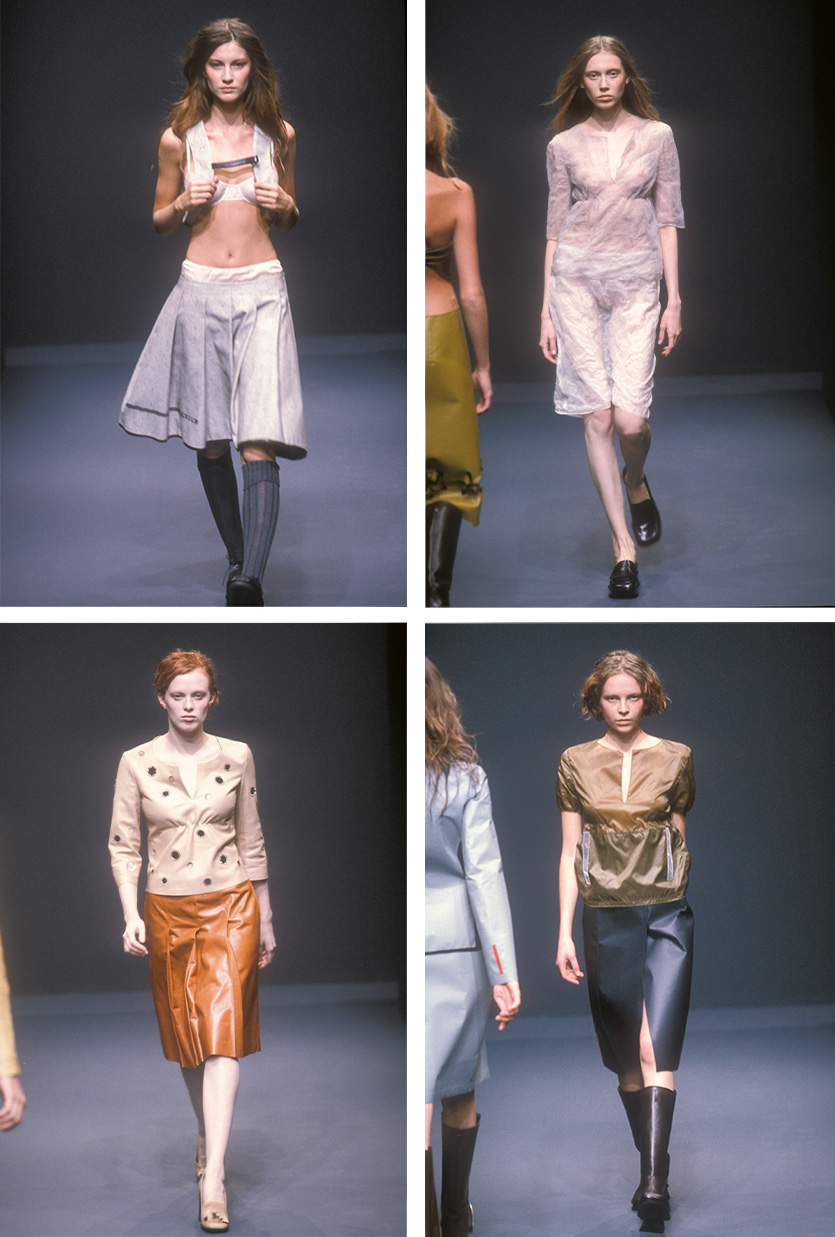

Ugly Chic’s break with the past was not as radical as it may have first seemed. The summer 1996 collection still contained lots of functional stretch elements, most notably the gabardine uniform fabric that Prada is so fond of using, paired with the finest cashmere and silk knits. The checkered kitchen-tablecloth patterns seem as though painted, in emulation of Paul Klee. Beneath were floral dresses redolent of industrially manufactured summer wear, but in fine silk, without frills and pleats, and hand-embroidered in the tradition of couture and folkloric garb.

Miuccia Prada’s materials were luxurious, including the thoroughly researched high-tech materials which, unlike more affordable synthetics, were substantial and lent themselves to plastic forms. The cut of the uniform itself returned to the PRADA catwalk in the form of narrow-fitting Space Age trouser suits. Ultimately, her Ugly Chic was an amalgamation of the 1960s dreams of the future, upper-class elegance, art world snobbery, and, previously seldom tapped, sources rooted in female popular culture. It merged good and bad taste, high and low: in short, Ugly Chic.

EXPLORING FEMALE POP CULTURE

It was Miuccia Prada’s exploration of the culture of everyday female culture that made her fashionradical. Although Gaultier had already shocked with his tampons, conical corsets, and scourers, hehad gone no further than the grotesque exaggeration of female attributes. Prada took this aspect ofculture seriously and instrumentalised these common attributes for avant-garde intervention.American Pop Art had drawn primarily on male attributes such as cars, pin-ups, and cannedproducts for bachelors. Prada, on the other hand, made the paraphernalia of the collective femalesubconscious art-worthy. In the winter of 1996–97, she followed this up with Constructivist all-overprints, reviving a lost tradition of industrial textile art that had been practised by women during theearly years of the Soviet Union, and later at the Bauhaus. Anni Albers’s dynamically patterned wallhangings spring to mind, as do artists such as Varvara Stepanova and Lyubov Popova, who workedin Soviet factories and revolutionised everyday life with their techno prints.

In the high-class world of western fashion, textile printing had been marginalised. Since it stood for industrialisation, mechanical reproduction, and cheap effects, it was anathema to the meticulously painstaking craftsmanship of the haute couture ateliers. While the ready-to-wear sector tolerated printed fabrics for summer, in the luxury bracket they were disdained for their repetitive monotony; furthermore, the patterns met inelegantly at the seams, revealing their mass production. Lively prints were restless, plastering the wearer like an advertising column, competing with her personal dignity. Traditionalists dismissed prints as soulless products of the machine age. Modernists railed against them as ornament; true to Adolf Loos, who took ornamentation for a mark of the criminal mind.

Avant-gardists of all stripes considered decorative elements as incompatible with modernity. TheBauhaus in its serially functional simplicity laid claim to good form as the epitome of moral superiority. Walter Benjamin identified useless ornamentation with the mentality of the Wilhelmine era and its efforts to bar its doors to industrialisation. For him, the cosiness of the middle-class parlour in 1880s Berlin was exclusive, since there was no place for visitors, every inch of space being covered with knick-knacks and trinkets. Needless to say, the aversion to jewelry and ornamentation harboured an aversion to the female sex. While the avant-garde of the early 20th century celebrated masculinity first and foremost as a challenge to the status quo of social fatigue, Benjamin targeted femininity more directly: his list of abhorrent objects falls clearly within the preserve of women and their homely arrangements.

Miuccia Prada set about liberating modernity’s feminine subconscious from repression, and became an archaeologist of female attire. In an interview, she said, “I often quote classic cuts: the 1940s jacket, the 1950s coat, the 1960s miniskirt—but I never change the form,” adding, “You might call that appropriation, but for me these designs symbolise certain moments in history, certain ways of being feminine, which is what I want to reference. I’m not interested in changing the origin of a cut.”

Generations of couturiers had tirelessly endeavored to be original. Miuccia Prada achieved this aim by making short shrift of it. Leaning towards appropriation art, she positioned herself as an intellectual operating on a conceptual level, and shifted attention from the design genius to the psyche of the consumer: “I often used these cuts to explore an idea or a concept relating to the obsessions of women.”

Prada’s comments place her designs in quotation marks, as though they were not about creative decisions regarding taste, but rather about riffs on themes brought to her by the cultural history of women. Instead of broadly avoiding the traditional decorative aspects of womenswear, as do minimalist designers like Jil Sander, Prada emphasises and on occasion even exaggerates them in her prints, lace, and appliqués, with a touch of sweetness and cuteness, while still lending her designs an avant-garde note through her use of classic masculine cuts. She has translated the obsessive aspect of female narcissism into an ironic attitude fully capable of embracing what the fashion police deem ugly. Within this context, it is only logical that Prada would speak out confidently against functionalism: “Who’s interested in whether something is comfortable? That is boring and uninspiring. It is neither exciting nor challenging. I find stiff and heavy materials majestic. They give women dignity and a sense of importance. They make them strong.”

A parallel could be drawn with Catholicism, the matriarchal religion of Italy, and its cult of suffering. Christianity, after all, is aware of something higher than well-being and worldly beauty. It strives to overcome earthly pleasures. For Christians and their Puritan forebears, one might say, ugliness carries the germ of exaltation, of the sublime. It qualifies as the profane manifestation of redemption.

A METAPOSITION OF DRESSING

Miuccia Prada proved that there could be discourse in dress. Whereas previously a woman had to opt either for the diverse roles of the weaker sex or for the authoritarian statement of androgynous power-dressing, Prada introduced the possibility of demonstrating an artful persona without turning it into a cliché. In designing modernised versions of the black Christian Dior suit at the beginning of her career, Prada tried to convince herself that there was a couture variety to the uniformity of her fellow protesters. Her next step was to show that the protest look did not have to be homogeneous. Above all, it shouldn’t be hypocritical; hypocrisy is, after all, the repression of one’s own background. That is why she wove all the weaknesses, neediness, and vanity of women of the bourgeois era into her Ugly Chic. She systematically tackled what had once brought them attention, but which had come to be seen as pompous after 1968: expensive guipure lace, amusing tourist prints, brocade, enticing transparency, circular skirts, sparkling costume jewelry, and impractical handbags.

Prada made this metaposition of dressing her personal mission: “I’m much more self-confident now.I’m far more willing to express myself freely and openly. That is why I now work a lot more with printed fabrics. I used to find prints difficult because they are so expressive. You can’t hide yourself behind them. I now use them to convey my thoughts and to communicate my ideas and concepts. I am prepared to take more risks, to reveal myself.” On the journey towards her own preferences and obsessions, the biggest hurdle had been camouflaging her very self, the temptation to hide behind minimalist coolness.

In the early years of the 21st century, her subversive fashion was distrusted as high fashion. The normcore generation preferred to play it safe with deliberately understated dressing. Rarely was the love of jewelry so scorned. People shunned the naïveté of ostentation that might express an uncorrected lust for life. Meanwhile, we have left this transitional phase behind us, and that is also thanks to Miuccia Prada. She was one of the first designers to approach clothes as political statements, noting their shortcomings and offering solutions. Her summer 2014 collection sent shockwaves through the fashion industry. She had taken her inspiration from the murals in SouthAmerican favelas and had graffiti artists paint faces on wide-cut shift dresses—an absolute faux pasin the world of high fashion. Her starting point had been a documentary film about ghettos, which made her aware that the desire for individuality in fashion was an elementary need, rather than an acquired habit of the privileged classes.

When Prada styled the American poet Amanda Gorman for her performance at Joe Biden’s 2021 presidential inauguration in a high-necked outfit comprising a quince-yellow suit teamed with a buttoned-up white blouse and a red hairband echoing a delicate 50s pillbox hat, the Milanese designer had well and truly arrived in pop culture. Contemporary taste had caught up with her idiosyncratic excursions into fashion history. The ecologically motivated avoidance of consumerism prompted those who were interested in fashion to trawl vintage outlets, discovering distinctive trends of the 20th century along with fabrics now rarely produced.

The non-serial, personally curated look has now been adopted by both men and women, including idiosyncratic hair and beard styles, partial shaving, braiding, and comically protruding plaits, along with exaggerated volumes, unorthodox trouser lengths, outrageous footwear, deliberate disproportionality, and every conceivable form of cross-dressing. On the streets of the big cities, the younger generations succeed in combining a cheerfully self-effacing nonchalance with an iconic self-image reminiscent of Second Life and cartoon characters. Considering Alessandro Michele’s energetic march through the opera archives for Gucci, or Demna Gvasalia’s VETEMENTS catwalk shows with their bizarre nightclub outfits and imaginative Eastern Bloc ersatz fashion, Prada’s design strategy has reached the mainstream.

We now find ourselves in the second, internet-determined phase of postmodernism, which dissolves the boundaries of time and space for everyone with a smartphone. The one-dimensional timeline of teleologically framed history is alien to this generation: it can barely imagine what it was like for citizens of the 20th century to feverishly anticipate news from the Paris catwalks. Today, the pioneers of fashion spread out in all possible historical and geographical directions, and what they bring back from these travels is not a trend that outlines a collective future, but quite simply something interesting. And, just as it should be in an unlimited present tense, elevated above “out”and “in,” nobody has to choose for integrity’s sake between minimalism and the libidinous desire for ornamentation.

The two opposite poles of Prada’s oeuvre interact and complement one another. When Miuccia first listened to her instincts and wore Yves Saint Laurent to a demo, she could hardly have foreseen the confusion she would trigger. A confusion which carried the seeds for the first true look of the 21st century.