If you want to talk about Helmut Lang, you have to start by talking about his chutzpah. Though he was from Austria, the terra incognita of the fashion world, he launched his label’s first runway show in fashion’s capital city, Paris. The list of things he was the first to do is so long that it sounds like a piece of conceptual art. Lang was one of the first designers to collaborate with artists. He was the first to include men’s and women’s fashion in the same show, worked closely with Juergen Teller to launch the innovative idea of backstage photography, and was the first to abandon the tradition of bowing to the audience at the end of the show. While his shows took on the super-show format, he was the first to do away with raised catwalks. Lang was also the first designer to send a fashion house across the Atlantic. He ensured that New York Fashion Week was held before any other, by holding his own runway show there weeks in advance.

He was the first to send out CDs instead of invitations to his shows, becoming the first designer to profile his collection online. Having turned the New York fashion calendar on its head, he then brought his show back to Paris, only to cancel it in the wake of 9/11. He was the first fashion designer to advertise on New York taxis. He was the first to create a unisex scent, the first to place fashion ads in unrelated magazines such as ARTFORUM and NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC. He was also the first designer who did not attend the American Council of Fashion award ceremony, even though he had been nominated in three categories and was actually in the city at the time.

His avant-garde status is proven, without so much as a word about his design. And although he sold the rights to his label in 2005 and gave up his position as chief designer in order to focus on being an artist, people still talk about his clothes. His style is woven out of contradictions: clean and complex, minimalist and epic, modern yet deeply rooted in the traditions of clothing. In approaching an oeuvre that has enthralled the fashion world for many years, I would like to focus on a number of aspects closely related to Lang’s personal biography. First of all, there are his younger years in Vienna, where he kept his head above water as a barman and waiter. Yet his childhood had been spent with his maternal grandparents in an Alpine valley in the province of Styria, where he would help his grandfather, a shoemaker, to make sturdy hiking boots. There, he mixed with ordinary people and came to view clothes as goods with a primarily functional quality. Color, decoration, and ornamentation were reserved for the traditional costumes known as Trachten and had nothing to do with fashion.

Another Vienna-related aspect of his aesthetic approach lies in the literary legacy of Arthur Schnitzler, still influential today, who wrote so fluently of sweet, flirtatious young girls and the sultry eroticism of fin-de-siècle Vienna. Although nothing may seem more alien to Lang, it cannot be denied that his oeuvre does include some classic traits of seduction. We should also bear in mind that Lang’s breakthrough as a designer coincided with the emergence of deconstructive text analysis. Deconstruction, translated into fashion design, became one of his central tenets. Even the genesis of Vienna’s metropolitan bourgeoisie against the backdrop of courtly tradition helped to shape Lang’s thought processes. Nobody has been so consistent in addressing the values represented by bourgeois apparel, nor so thorough in their contemplation of deportment and polite manners. Lang’s decision to opt out of fashion design and become an artist is also to be taken absolutely seriously.

His oeuvre has been shaped by his relationship with contemporary art: it would be easy to devote an entire exhibition to the way his designs correlate to the works of artists. And ultimately, when it comes to Helmut Lang, we cannot avoid talking about modernity. In this respect, Adolf Loos is an obvious point of reference. This influential Viennese architect, whose rhetoric railed against the ornamental, is effortlessly adopted, ad absurdum, in Helmut Lang’s fashion design. From zippers to shoelaces, Lang’s declension of the grammar of form is all-inclusive. Yet in the urban apparel he designed for those who spend their days in air-conditioned offices, studios, and airports, function becomes décor. The fact that Helmut Land was modern, both in spite of this and because of it, remains an enigma in the world of fashion. It might be said that he was able to hone such brilliant skills because of his observations as a waiter in his younger years. In any Viennese café, the waiter tends to be the best-dressed man in the room. He is also the most circumspect, discreet, and insightful person amid the collective euphoria of celebration and pleasure-seeking. That in itself made the former waiter Helmut Land precisely the right man for the exuberant 1990s. A waiter occupies his unstimulated mind by forming diagnoses, noting moods and clothing faux pas as well as social trends. Such a public venue gives him a good insight into a statistically interesting mix, and, with that, the ability to make well-founded forecasts. No matter whether Lang speaks of his guests.

Against this background, Lang’s sense of form and elegance is almost self-explanatory. In addition, his parents split up shortly after his birth and, at the age of five months, he was put in the care of his Polish grandfather and Slovenian grandmother in Ramsau. To this very day, Helmut Lang still speaks wistfully of his ten years in that mountain setting. The fascination of New York, where he later chose to live, was, he explains, rooted in the similarity between the skyscrapers and the Alpine peaks. It must have given him same sense of the sublime, that same awareness of the relative insignificance of the individual. What is more, everyone who wanted to survive in the raw climate of the mountains took their clothing seriously, dressed according to the weather conditions, and gave preference to tried and tested garments rather than the latest look. And besides, as the American sociologist and economist Thorstein Veblen notes in his THEORY OF THE LEISURE CLASS (1899), fashion is of little interest in static societies where everyone knows each other, knows the status of their neighbors, and can impress nobody with lavish outgoings. His Alpine childhood made Helmut Lang immune to fashion and independent of any form of up-dressing. One only has to imagine the freedom of the child in lederhosen, never wasting a single thought on what he should wear tomorrow.

Helmut Lang’s genuine interest in hard-wearing everyday clothing and workwear stems from his time in Styria. He has sought out traditional suppliers of clothing, including workplace uniforms. During his time in Vienna, he even designed overalls and work coats for a textile company based in Vorarlberg. For his own collections, he liked to use surplus textile stocks for synthetic workwear. And at the very apex of his career, one of his best-selling items was a pair of women’s trousers based on the staff uniforms of the British John Lewis department store chain. As a designer, he was also very keen on Aertex and its patented cotton-weave items. In taking inspiration from such sources, he was following in the footsteps of Coco Chanel, whose Little Black Dress was inspired by the uniforms of the room maids at the Ritz in Paris. Helmut Lang is rarely seen without his Levi 501s, and it was his love of blue jeans that lay behind the creation of his own best-selling jeans line. This classic garment, originally intended as robust rural wear, seems to have created a bridge for Lang between Alpine life and the world of American pop. His move to New York further underlined that connection with denim.

Even more than for others of his generation in Vienna, Helmut Lang saw America as the land of childhood, adventure, and liberation from the Viennese academic pressures that he had undergone as an accountancy student at business college. Above all, he liked the original jeans of the Gold Rush legend. After all, he too was a self-made man, a dishwasher turned millionaire: “Denim should remain original. If I had no commercial constraints,” he once said in an interview, “I would work on heavy, indigo-dyed jeans.” Thanks to Lang’s penchant for solid textiles and workmanship, his interviews for TEXTILWIRTSCHAFT magazine are among his best. He dives into the terminology of the textile specialist with relish: “In the ’80s, we had a tendency towards lightweight materials. There were hardly any decent goods,” he told the magazine in 1996, adding that “I personally wish that we would see a return to valuing fabrics’ structures.” Two years later, he told the magazine that “We are currently working with very traditional fabrics and traditional craftsmanship. Our suits are hand-made.”

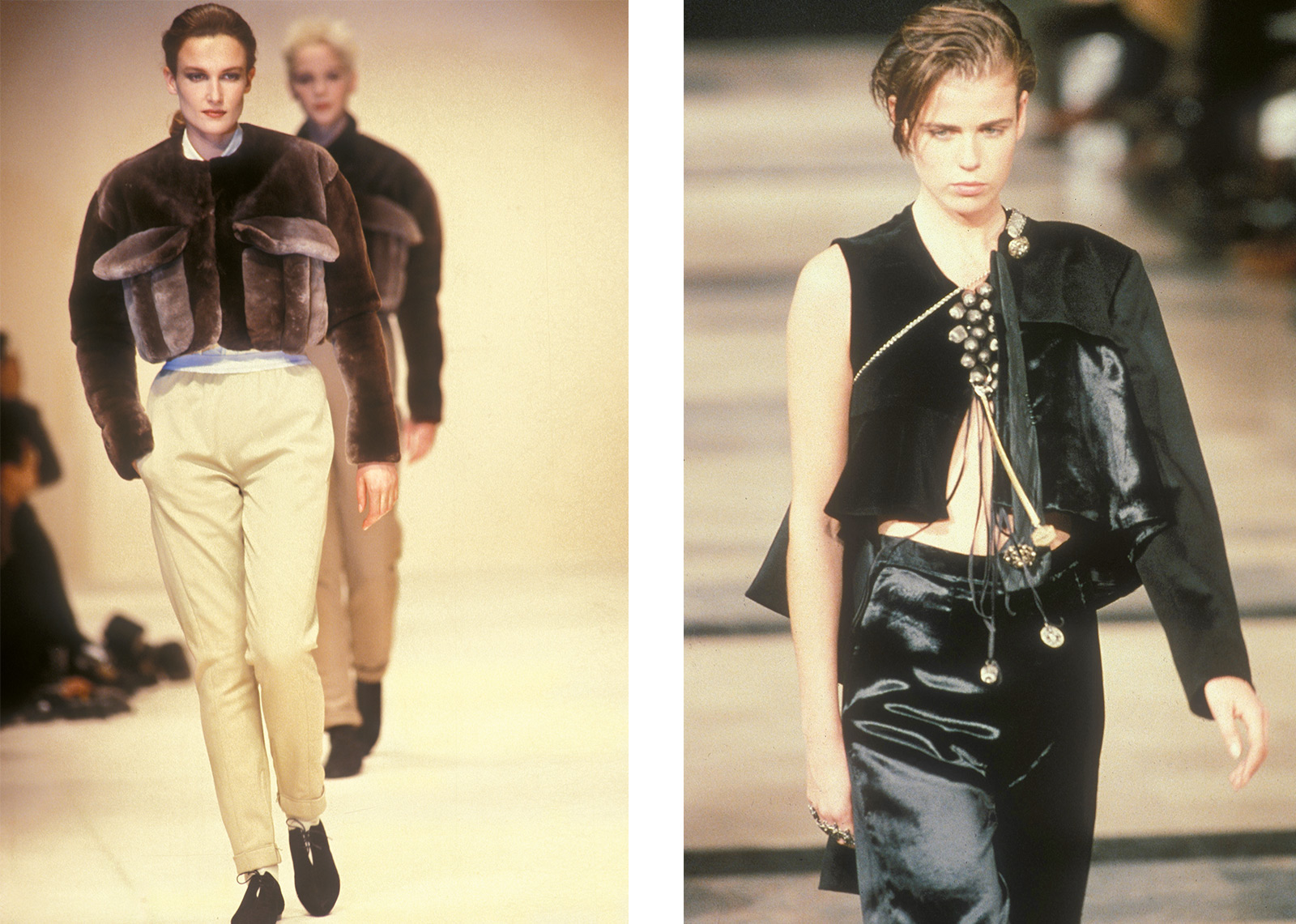

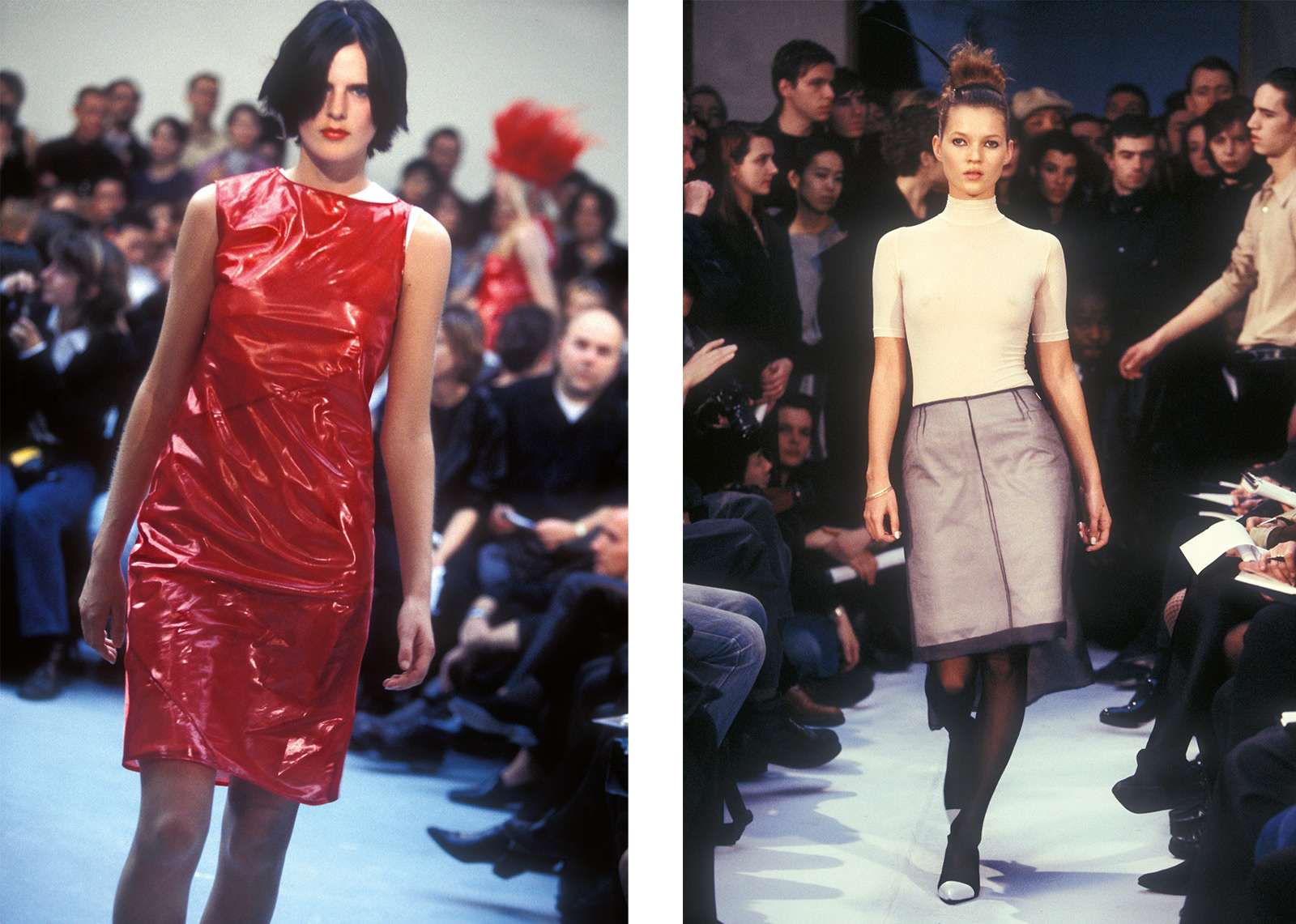

HELMUT LANG, Autumn/Winter 1990

In 1966, shortly after the death of his mother, the ten-year-old Helmut Lang was taken back to Vienna by his father, a truck driver. He was unhappy there and this was further compounded by his stepmother, who made him wear the suits of her late father. In those days, young men were protesting in Vietnam parkas from US Army surplus supplies, in Marlon Brando T-shirts, old leather biker jackets, and jeans. This pre-grunge era, which Lang observed with admiration and helpless envy, sowed the seeds of his subtle sense of eroticism and his incomparable come-undone look. Yet there is also something specifically Viennese that played a role in his dérangé aesthetic, rooted in the nomadic spirit of the people who once roamed the Carpathian steppe directly beyond the city bounds. This wilder Carpathian culture is still very much alive in bohemian circles there. And Lang, too, had a soft spot for the pragmatically garbed and mirrorless wandering people. After all, in a certain sense, in spite of his sheltered life, he himself had been a motherless nomad since he was five months old.

When the S&M look started to become fashionable in the late 90s, Lang was already miles ahead of the sultry déshabillé look. As the child of a city where the atmosphere was impregnated by Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt, and where hotel rooms could be rented by the hour, he opted against luxurious sheerness and went instead for beautiful, vibrant disarray, with men’s fabric trousers that shifted at interesting angles, overlapping asymmetries, and fluttering angular hems. Lang’s language of sensuality is neither lewd nor clichéd, and is anything but misogynistic. When he used suspenders in the most unlikely places, they were as proper and efficient as only a parlor maid would perceive them. Or a May Queen, waving her brightly colored ribbons. Lang created his key looks with the ceremoniously attentive eye of the waiter going about his work while others celebrate. Even at his first show, during the exhibition on Viennese modernism — “Vienne 1880– 1938: L’Apocalypse joyeuse” — at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the dirndl-inspired corsages that he presented were dyed black like a waiter’s uniform. That was very elegant, and summed up everything he believed in.

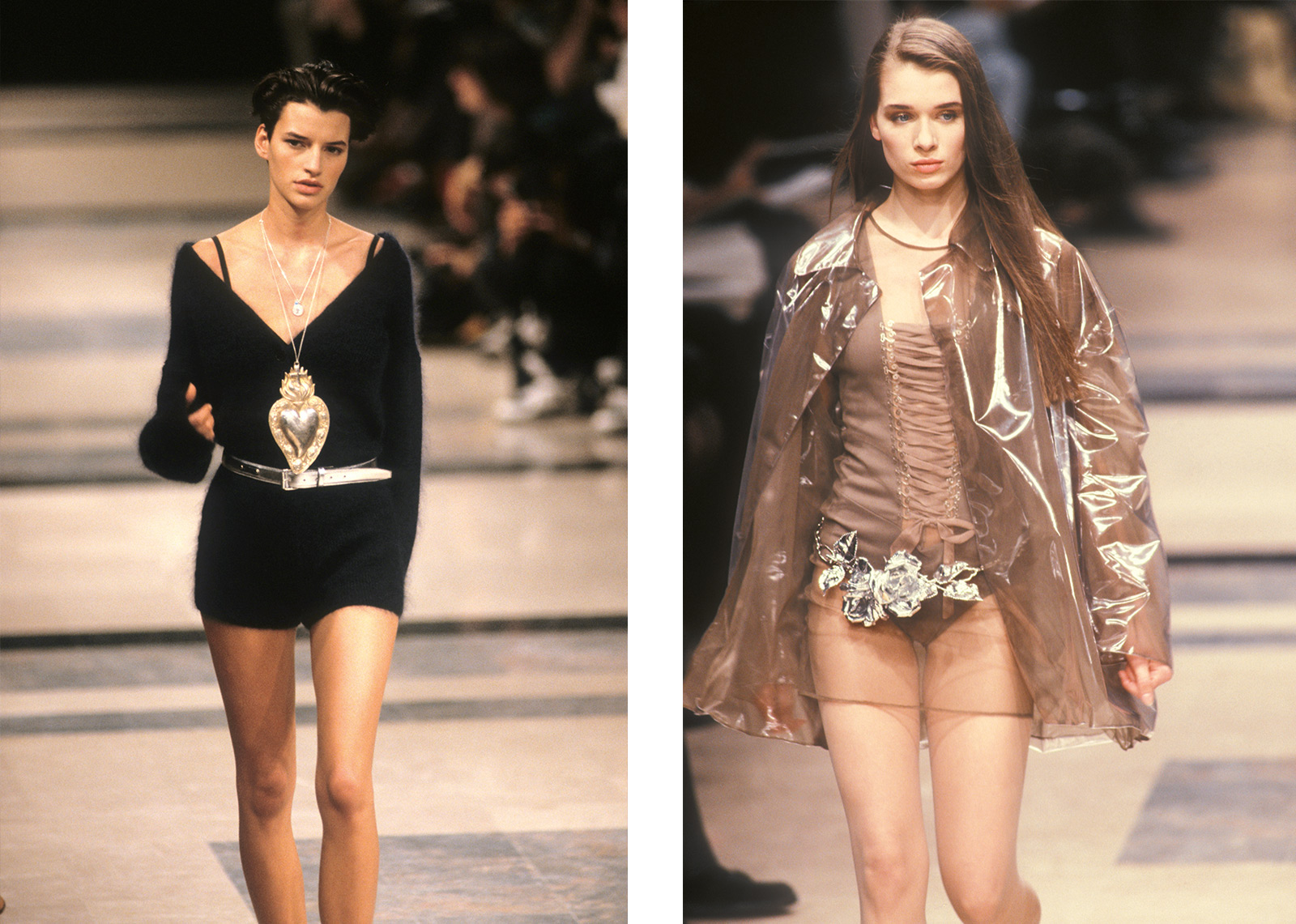

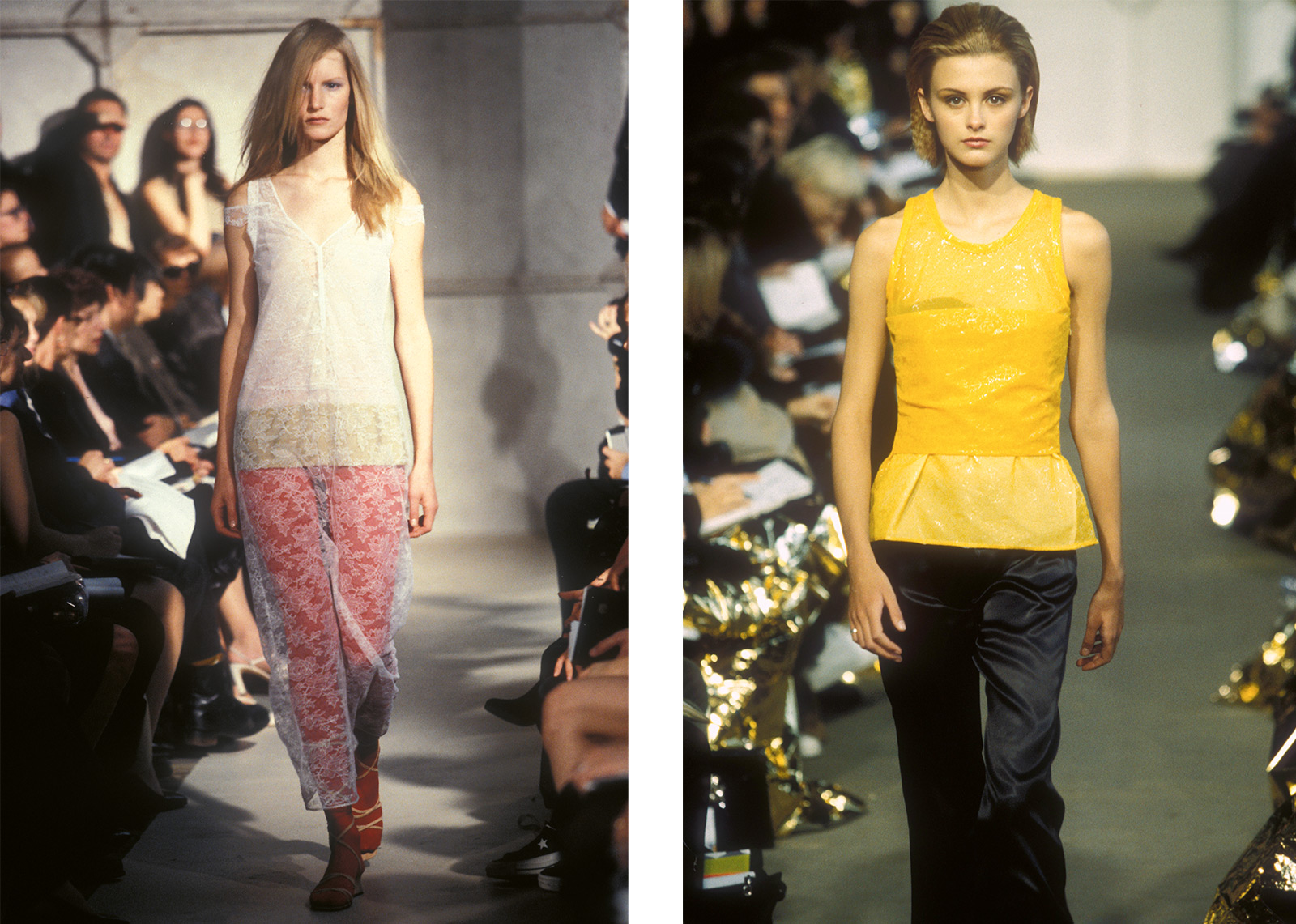

HELMUT LANG, Spring/Summer 1991

In his designs, Helmut Lang took a methodical approach to eroticism, and there was clearly a formula. He conceptualised sensuality, conceiving of it as the emergence of the instinctive in formal attire. Lang is a smart behavioral psychologist who is always interested in the visual only as a function of what it triggers in the observer. His art of conditioning is one that eschews pornographic effects in a bid to achieve his wish for a lowering of weapons in the modern trench warfare of egos, a moment of empathy, emotional openness, and light-hearted relief. This, he knew, was the only way for bonds and sensual curiosity to form. “The bust has to be perceptible,” he said. “And the hips. A bust is perceptible if the man looking at it already believes he has touched it. A woman achieves that by wearing a dress that is a size too small.” Lang himself likes to wear close-fitting clothes. “I like clothing that has been worn in. I relate to it then.” Clothing that has come to fit the body through habitual use, and encloses it, lets the wearer develop an erotic rapport to the self, recognising and relating to this wearable alter ego in a tactile way. What is more, well-worn clothing takes on the scent of the wearer and, as such, is like a large perfume pad. Together with Jenny Holzer, Lang did actually develop a perfume intended to capture the fragrances of a turbulent night of love. “A blend of fresh shirts, dirty sheets and sperm,” is how Jenny Holzer described it. “It is like being able to smell the soul,” adds the designer. And the soul is something eminently erotic for Helmut Lang. Asked whether he could envisage his label being continued by a team of designers, he replied, “The soul can’t be copied.”

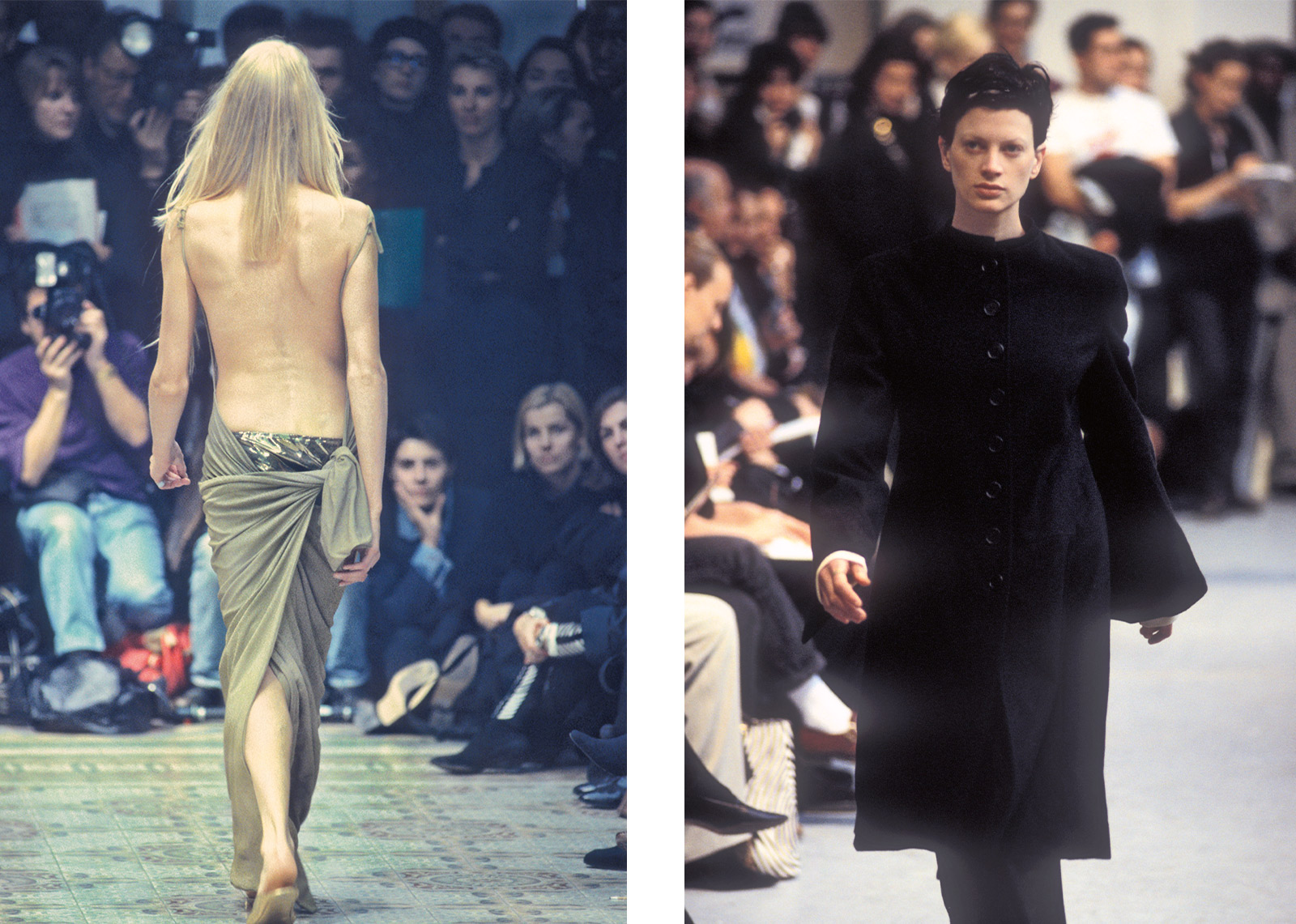

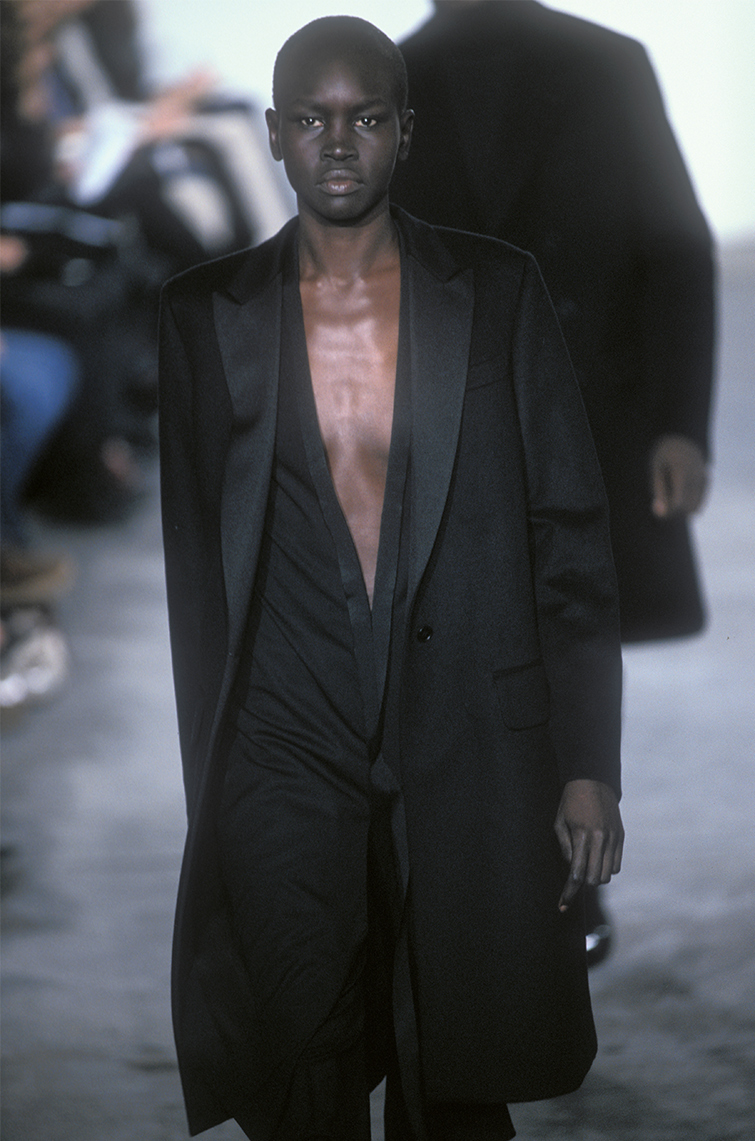

HELMUT LANG, Autumn/Winter 1993

Given that, for Helmut Lang, everything centers around emotions, he has turned the vocabulary of minimalism on its head and superimposed a private language of bewilderingly diffuse signals. Few have noticed that this is about the classic repertoire of seduction, so prevalent from the Rococo to the girl in the Prater park. Teasing, coquettishness, and innuendo are Lang’s veritable element. It is a game that masks his extremely civilised and very humane fundamental outlook. His fashion seems liberating because the perplexing impossibility of pinpointing its position within a cosmopolitan world actually protects against the over-hasty projections and prejudices of others. This is where the power of fashion lies, for as long as it creates something new and does not seek to classify, it always gives freedom. The artist in Lang has always been interested in this aspect.

During the 2000s, he approached the complexity of ambiguity by borrowing from the world of flora and fauna. He told French VOGUE that he read works about natural history. His monochromatic looks are the children of nature’s camouflage, in much the same way that it is also reflected in mountain clothing and hunting wear. Lang’s fascination with insects led him to create damp-looking surface finishes and thermal textiles that change color on the body, as well as shimmering polyester tops with underlying patterns reminiscent of the neural pathways of dragonflies. He also loves washed-out prints like the forms left by dried blossoms pasted onto paper. He has used these for T-shirt dresses covered in sheer fabric. While mimetic camouflage promises protection by making the masquerading creature appear innocuous, what is known as Batesian mimicry protects a harmless creature against predation by making them look like a member of another, poisonous species — often through the use of toxic coloration. Lang is a virtuoso in using toxic green, searing pink, and garish orange for an elegance that the wearer only embraces because Lang disguises it as pop.

The loose bands he calls “extensions” are carefully hemmed strips of material applied, as with US Army parkas, to the inside of the garment. When we talk of extensions, we might think of Marshall McLuhan, who regarded technical innovations as extensions of human limbs. But, for Lang, the bands have little to do with progress. Rather, they are the feelers that the soul puts out when it dares to venture out from its modern snail shell. For Lang, sexuality, including its emergence and orientation, is always in a state of limbo, just as it tends to be in the case of intelligent beings. He put men in chaste slim-cut trousers with corset lacing, and dressed women in rubber lace and smart skirts with tulip hems just a little too narrow not to evoke thoughts of bondage. When Lang uses wet looks, there is no hint of sweatiness, but instead the pools of light flickering across the body seem like an expression of personality in the form of a subtle halo worn directly on the body. The fluidity of the reflections playing on a silk tulle dress worn by Tatjana Patitz in Lang’s spring/summer 2000 show (see p. 228) bore a striking resemblance to Gerhard Richter’s EMA (NUDE ON A STAIRCASE) (1992).

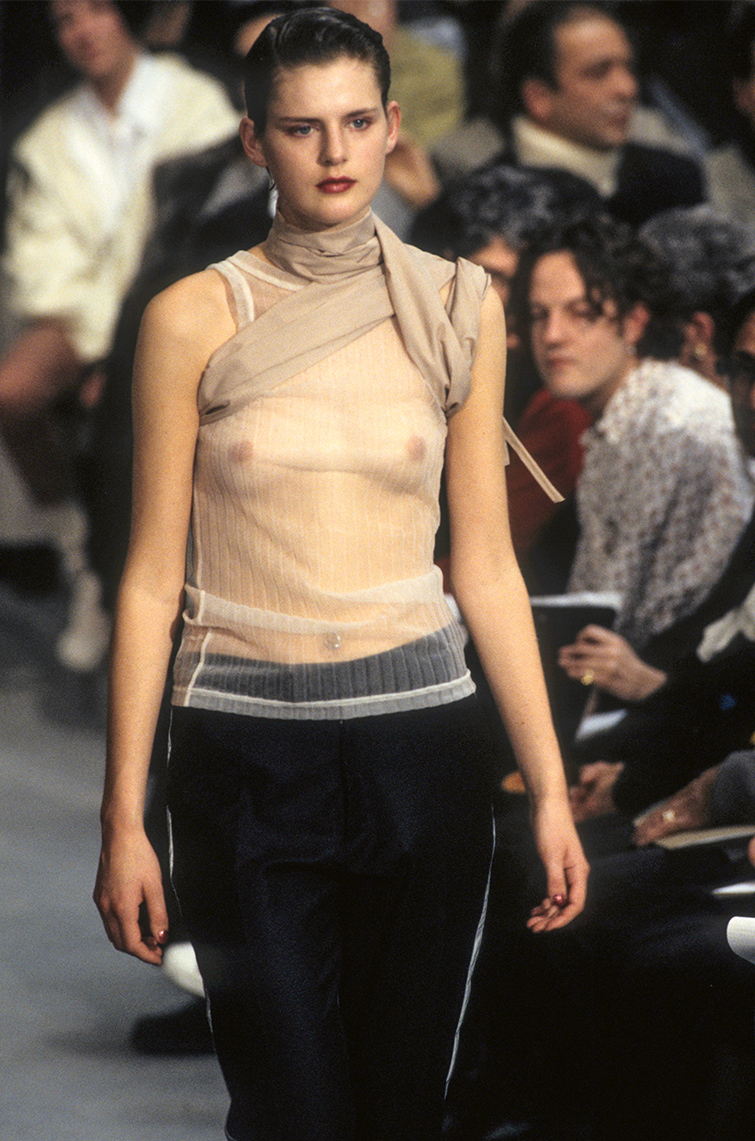

When Lang reacted to the S&M boom, he rhymed the words bondage and bandage, and crisscrossed bands of stretch material across the female chest in a way reminiscent of some kind of orthopedic aid. Arnulf Rainer’s Christ overpaintings also spring to mind here. Given that these bandage looks generally imply disability, wordless communication is involved. Empathy sets in, as it does to some extent with the kimono, which Lang, incidentally, also deconstructed. A willingness to help is aroused, only to fade again immediately in view of the prevailingly athletic component of the look. The observer does not need to save or assist anyone, but for a fleeting moment wanted to. What made the architectural symmetry of the 2001 bondage tops so ultra-sexy was precisely the fact that it was impossible to decide whether this was perhaps simply the creation of a purely functional aerobics accessory. At the same time, Lang made the female belly an erogenous zone by baring and framing it from the hips to the ribcage. The bands running diagonally across the breast area appeared like X-ray images. In this way, the designer hinted discreetly at the human skeleton and the goth movement fused with porno-chic.

Such sleights of hand show the deconstructivist on top form. What he worked on more than anything else was the man’s suit. And Helmut Lang knows what a repressive suit is. Instead of completely feminising it, as Hedi Slimane later did, he retained the boxy, almost paternal structure. “The aim,” he noted with his tendency to express things in the language of a manifesto, “is to waste no energy reinventing the jacket.” For him, the suit still had something of the broad-shouldered masculinity embodied by Elvis stepping up to the microphone. Except that Lang changed the collar, shortened or lengthened it, modernised the arm or the lining, and created a product that has a nostalgic yearning for the ironic, pre-military spirit of the ’60s in its DNA. This was not so much about a generational conflict as it was about protesting against the off-the-peg suit and about the kind of masculinity he saw in the Savile Row tailoring of Sean Connery’s 007 suits. It is as though the endless deconstruction and reconstruction of the man’s suit was Lang’s way of mitigating the shame and trauma of having to wear his step-grandfather’s hand-medowns. His obsession with the suit is reminiscent of Freud’s war invalids, who continued to dream of the horrors of the First World War even after it ended, in order, according to Freud, subconsciously to arm themselves against them. Lang also took his revenge on mass-produced clothing by applying diligence, offbeat sex appeal, modern sensitivity, and pure quality. All of which can easily be read as his commentary on fathers.

HELMUT LANG, Autumn/Winter 1995

Which brings us to the politics of dress. The suit is the very epitome of democratic garb, popularised by the French Revolution. It emphasises equality, dampens envy and snobbery, and acts in effect as a de-escalating and trustworthy collective uniform. The fact that it has been anachronistic since the late ’60s makes it no less appealing to Helmut Lang. On the contrary. What he has said about basics also applies to the suit: “Basics are textile rights that are not seasonal. They have the right to refuse to make a fashion statement.” When the dotcom generation opted for Helmut Lang’s suits, the swarm aspect undoubtedly played a role. As a traditional democratic outfit, it even appealed to flat networks.Well cut from quality fabrics, a Helmut Lang suit not only shows respect for the wearer, but also adheres to a fundamental sense of courtesy that, for others, is pleasing to the eye without overtaxing their aesthetic sensibilities.

The same can also be said of Lang’s urban basics, with which he created the metrosexual man, who could be elegant without becoming a walking icon of pathos. The experimental psychologist John C. Flügel described the era of the suit as a time of great male abstinence. Yet there is a difference between reluctantly feigning solidarity in the shared renunciation of dandyism and actually showcasing clothes aesthetically in celebration of this newly won democratic freedom. Doing so requires not only an ability to analyse the code of equality and adapt it to one’s own body, but also a willingness, expressed in the form of understatement, to give space to others. Fashion, as Lang once said, is not a question of aesthetics, but of attitude. In other words, it is only when you understand what makes people tick that you can dress tactfully.

HELMUT LANG, Autumn/Winter 1996

Of course, it is clear to Helmut Lang that increased respect for shared values ultimately leads to greater distinction: “Clothing is a definition of status. That has not changed.” Lang’s modernity is based on the fact that he does not exclude courtly form from the democratic dispositif. We should not forget that, in democracy, each individual is sovereign. And nobody knows better than the Viennese that, even among those who are equal according to the law, the one who is pleasing to others gets ahead better. “From the social circles I have frequented,” says Lang, “I learned that things should be approached with caution.” The way he puts together, or even pulls together, his suits, T-shirt dresses, and urban utility looks conjures up the hardbody of modern rivalry struggles. Yet his expertise in ornamentation, with all his extensions, bandages, cut-outs, and easily undone lacing, pays service to a different world view. They hark back to the courtly gallantry of a static society. “To grow up under really simple circumstances, and to understand that certain things were ornamental — the idea of the simple life interrupted by the opulence of particular festivities — that made an impression on me as a child and is something I use.” Helmut Lang has shown that the ornamental, so despised by Adolf Loos, does indeed fulfill an important function in terms of sensual communication. He would also subscribe to Veblen’s observation that traditional costumes are more likely to meet aesthetic criteria than passing fashions fads, for the simple reason that they are independent of the strategic need for distinction, having been honed and perfected over the course of centuries. “In the mountains, there was a very elegant way about basic necessities, a great beauty in a certain way that is completely refined but not about money.”

What Helmut Lang adds to the streamlined form of cultural reminiscences is barely identifiable and infinitely deconstructed. He embeds them within a monochromatic palette of skin tones and natural hues, including beige and sheep’s-wool yellow, chalky, ivory, and grey tones, and within the contrast between shimmering and matte materials, between high and low tech, softness and solidity. Yet when Lang speaks of his designs as “compositions,” he is referring to more than just an affinity with, say, Robert Ryman or Kazimir Malevich. For what he has created is a clothing-specific monochrome that relates to the forward-looking fusion of the historic driftwood of western clothing traditions and customs. He has merged these relics with his own athletic and elegant style, thereby saving them from obsolescence. With Helmut Lang, it has always been impossible to distinguish between the ornamental and the utilitarian. He has designed monochromatic traditional costumes and flamboyant uniforms alike, reflecting a society of increasingly abstract and cerebral activity. He reacted subtly to the desire for role-play and the flash of physical virtuosity that commands respect. But instead of wallowing in a carnival of vintage fashion quotes, Lang invariably also offered an insight into the impossibility of returning to pre-industrial, pre-digital spectacle.

The fact that he insisted on recruiting some of his models from Vienna’s bohemian circles is another aspect of this fragmentation. These Viennese acquaintances, who did not comply with accepted standards of beauty, reflected the melancholy that pervades all of Lang’s designs. “I like beauty at second glance, and the aesthetic that is broken then built up again.” His clothes are very young and very old, wounded, experienced. For that precise reason, Helmut Lang is no minimalist. It is also the reason why he understands modernism so well. He looked to British pop culture for the fluctuations of history and time that are inherent in his designs. “There came a breaking point in the fashion world,” he said in 1995, “which was when English magazines such as i-D and THE FACE presented people whose look expressed not only the power of beauty, but also the power of a personality shaped by fragility and inner brokenness. That took hold. And I reckoned we could go on working like this.

Lang’s melancholic design approach lay on the same frequency as that of pop song lyrics. Like those, he kicked up a storm against the enlightened sobriety of late capitalism, without torpedoing himself out of the equation right from the start by indulging in nostalgic kitsch. Yet, beneath the camouflage of functional competence lay a proliferation of fairytales on which the mobile armies of liberalism would surreptitiously feed. There is an arm’s-length re-entry list of utilitarian clothing elements he has poeticised. He became notorious for transforming halters, parachute harnesses, backpack straps, and holsters into a clean-cut bondage effect. Even a falconer’s arm-sheath was part of the mix. He used ski-boot straps to define his looks based on integrated accessories. Lang has also paid homage to old-fashioned attributes of clothing management, such as the sleeve protectors and sleeve suspenders worn by clerks, or the shoulder pads that he applied on the outside of the garment, as well as garters, fasteners, trouser bands, gaiters, and thumb-hooks for sweater sleeves. He likes the techniques of rural needlework and durability, such as padding, impregnating, and waxing garments, rooted as they are in a tradition of carefulness. These also include the patched trousers, some with contrasting crotch colors, and the cowboy-style chaps that Lang has presented being worn over formal evening-suit trousers. All of these have an inherent romanticism and a touching illusion of fashion naïveté.

However, Helmut Lang has also plundered the reserves of maternal femininity, helping himself to discarded household accessories, aprons, bibs, bodices, and slippers, and liberating them from their floral tat. And, since the history of female work clothes yields so little, Lang has instead appropriated women’s traditional costumes and status garments such as girdles, dirndls, the elongated and slit sleeves of the Renaissance, the crinolines of the Victorian era, and even Madonna-like veils. As for male work clothes, his stylistic recycling has included police vests, boxer shorts, lab coats, doctors’ coats, beekeepers’ hats, and trousers for sailors, painters, and builders, as well as sturdy twill boiler suits, fur-lined architects’ jackets, and pastors’ frocks. From the realms of modern myths of freedom, we find saddlebags and bullet belts, as well as outdoor looks adopted from surfers, polar explorers, astronauts, bikers, and goatherds. From the world of the military, he took GI shoulder flaps and the ubiquitous zipper, and from the splendid collections of the Imperial and Royal Army, he adopted sashes transformed into body bags and huge parka-style collars that hang loosely from the shoulder in the style of a hussar’s coat.

One runway prop that looked like the solid silver breastplate of a medieval knight turned out to be, in fact, a butchery trade utensil Last but not least, we have the Helmut Lang sleeping-bag cape. That one comes from pop festival culture. Woodstock was a defining moment for his generation. Helmut Lang cultivated friendships with artists from an early age. As a designer, he worked closely with the photographer Elfie Semotan, a graduate of Vienna’s School of Fashion Design. Her husband, the painter Kurt Kocherscheidt, became an important friend for Lang. The couple even reserved a guest room just for him at their farmhouse. The body perfume for the 1996 Florence Biennale marked the beginning of his collaboration with Jenny Holzer, whose conceptual art accompanied the visual asceticism of his first Helmut Lang perfume campaign. Later, Jenny Holzer went on to kit out Helmut Lang’s Soho shops with her LED works. Together with Holzer, Lang, and Louise Bourgeois, the Kunsthalle Wien launched a 1998 show devoted to the human body.

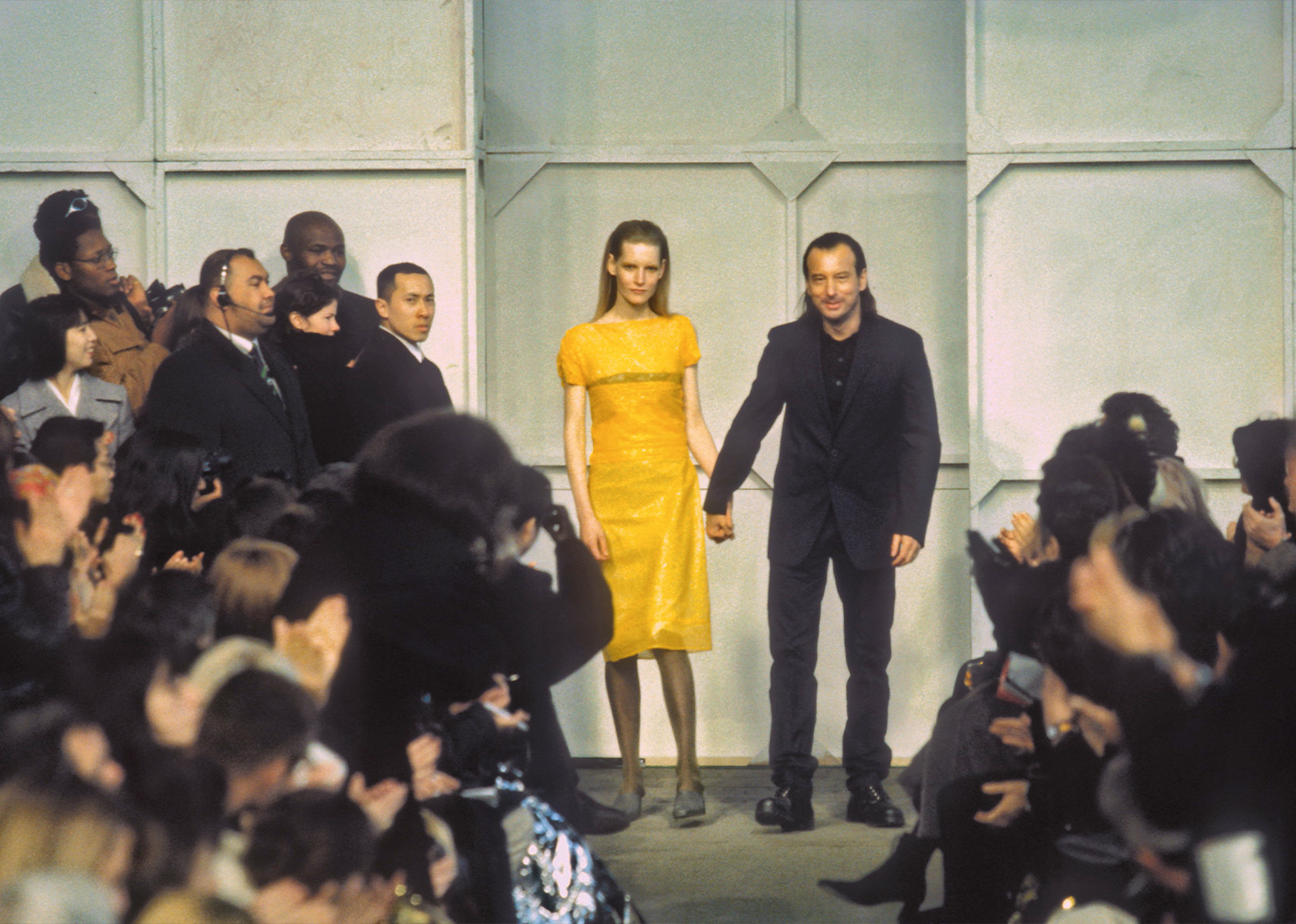

HELMUT LANG, Autumn/Winter 2000

It is remarkable that someone who treads their own path so steadfastly would speak time and again of insecurities. According to Lang, the Catholic school he attended in Vienna gave him a feeling of personal worthlessness and a large portion of guilt. Elfie Semotan once said of him, “Helmut made me believe that there was no profession worse than that of fashion designer.” Some of Lang’s seemingly downright arrogant statements can only be explained by a certain disdain for his profession. “People buy my suits,” he once said, “because they know that everything I have done has always been right.” He let these words pass his lips because he basically regarded the notion of infallibility in fashion as almost meaningless. At the same time, this self-doubt allowed him to take an uncompromising approach, free from wider vanities. In his development of textiles, his experiments with coatings for fabrics and using high-tech materials such as paper, bubble wrap, metallic mesh, latex, interlock nylon, faux fur, and cellophane, he took just as few shortcuts as he did in selecting first-class natural materials. Helmut Lang lacquered silk, added an athletic touch to Le Smoking by incorporating stretch materials, and didn’t even bat an eyelid at merging the old-school elegance of organza, moiré, faille, silk tulle, and crêpe with classically male materials, plastic, fleece, and patent leather. In order to achieve the look of leather, he had silk overdyed, lacquered, brushed, and polished according to traditional Chinese methods. He even lacquered jersey and used plastic sticks to construct a pair of trousers. In all of this, what was foremost in his mind was not his turnover, but his next experiment. His aficionados were unperturbed by such luxury, even though, by the late ’90s, the price of an ultra-thin cashmere pullover was $2,145. Before Takashi Murakami stared painting outrageously expensive bags for Louis Vuitton, Helmut Lang’s clients were already paying for the artistic dimension of his designs. He willingly paid out for clothing developed at enormous financial risk using often expensive resources. But he was investing with eyes wide open, for his design input was reflected in the resulting clothes, which were as exciting and as difficult to analyse as any modern work of art.

By the age of fifty, Helmut Lang had already achieved everything in his career: an iconic oeuvre, a global name, and financial security. Yet inner contentment was something he only spoke of after moving to Manhattan and buying a farm in East Hampton, where he lives with his long-term partner Edward Pavlick. What he has always sought, even in clothing, is stability. Friends have often noted this about Lang, and it has also caught the attention of others outside his close circle. “I’ll never forget how calm he was in the eye of this major storm,” recalls the American fashion agent Ed Filipowski, referring to Lang’s first New York runway show during a torrential downpour. Consistency and steadfastness were instilled in Lang while he lived with his grandparents. They didn’t even have a telephone. Life in Ramsau had barely changed in centuries. The fact that Lang ranked among the avant-garde of progressive fashion design was, ironically, the proof he needed that his wayward parents had made a cardinal error in abandoning him. His mastery of the new served in praise of responsibility and continuity.

Helmut Lang owes much to his close collaboration with Melanie Ward. So fully did he place her in the spotlight as his creative director that she became the very first star stylist, placing the focus on a profession that has now become an integral part of every collection presentation. Melanie Ward had previously worked in London for the same photographers and grungy magazines whose fashion portraits showing the broken beauty of a generation had so fascinated Lang. Together, they developed the look for the young adults of the ’90s, featuring a bewildering balance between urban athleticism and melancholy dishevelment, the clean-cut and the lyrical. Time and again, they succeeded in translating complex situations into simple solutions. They understood the need for clothes for young women who wanted to be smart and feminine without the stiletto heels and broad shoulders their mothers wore. And they understood that the male sex was willing to show sensitivity without turning into Las Vegas lounge lizards. And so Lang and Ward created a new elegance that became the testing point for the hip-hop maximalism of the 2000s, especially with Lang selling his company to Prada during that time. “I never wanted to be employed in the service of mass taste,” said the designer in a 1996 interview. Yet at the very moment when mass taste was turning its back on the refined understatement of the likes of Helmut Lang, he was heading towards expansion.

Given his quietly reserved attitude, there was no sign of panic with this designer. “Do not worry!” he said in 1998, citing the exact verse from the Gospel of Luke. In 2001 he said, “It would be possible for me to stop at any point.” He hoped that the collaboration with Prada would give him more free time for creative processes. “Mostly,” he said in retrospect, “it has been about surviving day to day. The intensity of it takes years away from your personal life.” Elfie Semotan moved to New York with Lang and her observations were not without concern. “His work was really exhausting. I knew that he loved it, and would keep on doing it, but at the same time it was clear to me that he did not want to devote himself completely. He did not want to be consumed by the fashion world.” In order to formulate ideas, Lang needed downtime doing nothing. “That’s when everything happens,” he said. But in the midst of the digital revolution, it was almost impossible for a top designer to lose touch with his management team for even a few hours. And so it was that, from one day to the next, he chose the great boredom of leaving the fashion world behind. “For me, it was always about the next biggest circle of freedom.” To paraphrase Eric Wilson, commenting in THE NEW YORK TIMES about Helmut Lang’s departure: because he cultivated the image of a fashion designer whose success was based on being above fashion, some of Lang’s admirers believed that he would become a rock star in the history of fashion, remembered as a legend rather than a failure.