DANIEL BAUMANN: In the exhibition “David Armstrong” at Kunsthalle Zürich we exhibited early photographs from the mid-1970s, taken when he was in his late teens. The works show young people hanging out in and around Boston at the time when David was studying at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Lisa, you’re in some of these pictures. You knew David, as well as Nan Goldin, from very early on. Can you tell us how you met him?

LISA LOVE: I met David when I was 18 years old. I was in the lobby of the Museum School next to the cigarette machine. I was waiting to show my work to the painting department and he stopped to say hello. We became very close, and he introduced me to everyone. I probably was much more conservative than most everyone at that time. I spent a lot of time driving David around. I think I was the only one with a driver’s license. Originally David was a painter so we spent time in the painting studio together. Ultimately he gravitated towards photography. He was incredibly talented when it came to finding the light. That was always the case from the beginning. He found the light. He was always dressing up. David just had an innate sense of style, an eye for beauty. Then we all graduated and moved to NY. I had been photographed by Arthur Elgort for NEW YORK MAGAZINE and after that went to Paris. I saw little of David in the 80s, and he wasn’t taking fashion photos yet. That wasn’t until the 90s. By then I had already left for Los Angeles.

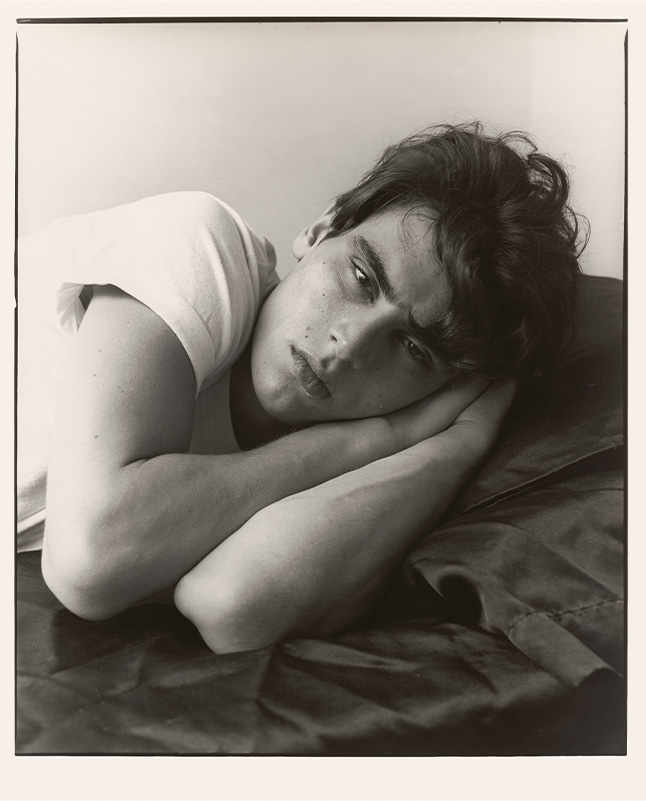

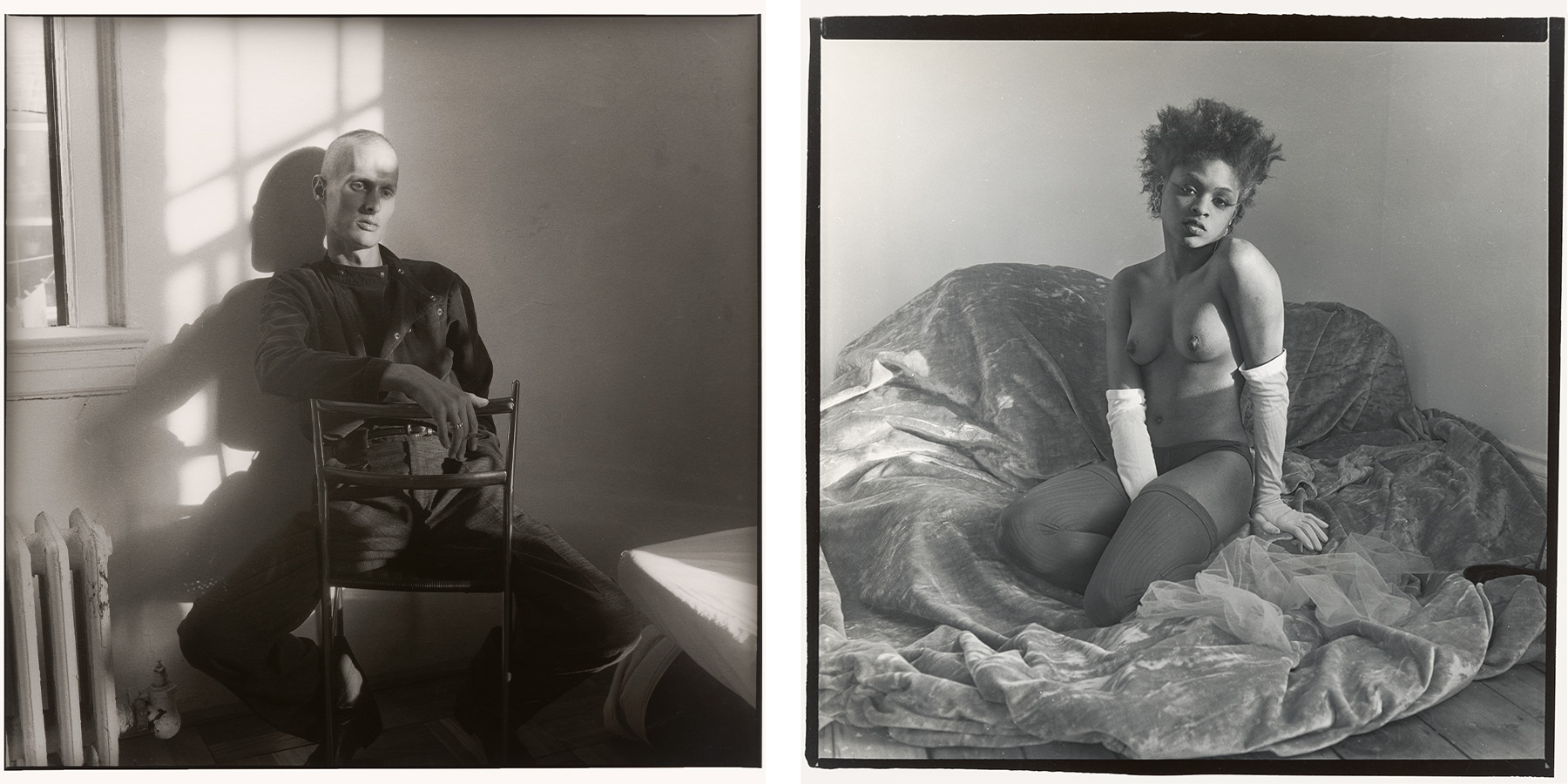

Kevin at St.Luke's Place, New York City, 1977

BAUMANN: Looking at the portraits of so many different people, one has the impression that they all enjoyed being photographed by David. Why was this?

LOVE: The connection between subject and photographer can be magical. An intimate feeling breaks through sometimes, and there’s no other feeling like it. It’s an intimacy that makes them love the moment. So maybe they enjoyed it—or maybe David found the light and beauty in the picture beautiful. It’s very painterly really. It was his choice in the end.

BAUMANN: Someone told me that he portrayed his friends without the mess of their lives, but in all their beauty. Looking at these pictures in 2024, Armstrong also painted a portrait of a scene, of a moment in time in New York in the 1980s. Did it feel like that back then? Or was it more that he was just taking pictures, and later it turned out to be a scene? What do you think, Wade?

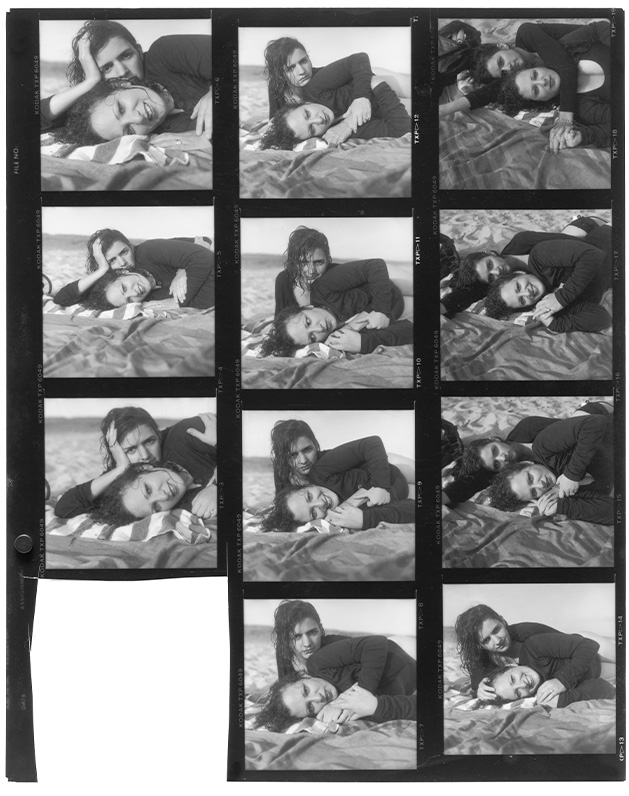

WADE GUYTON: I’m not sure I can speak to the scene as I’m younger and was never a part of it. Regarding intimacy though, the thing I noticed after installing the show, after seeing so many photos and faces simultaneously—and this is something I didn’t really understand from looking at his photos in boxes or in books—was this look that goes back and forth between David and the subject. The intimacy goes both ways. David was a captivating person himself and I’m not surprised that his subjects were also enthralled with him. I was talking about this with the photographer Miranda Lichtenstein and she remarked that this made sense: in the 1970s and 80s David was shooting with a twin-lens-reflex medium-format camera, and physically that camera is held lower. So he’s looking down into the camera to focus, and then back up at the subject. Unlike with a 35mm camera, which you hold up to your eye, with a TLR nothing gets in the way of David looking at and talking to his subjects. I’d never thought about the technology and how it produces a different relationship to the subject. But you can sense the difference in the earlier candid photos taken with the 35mm.

LOVE: That’s so true Wade!

BAUMANN: Wade, how did you get to know David?

GUYTON: I met David in 1996 in New York, through our mutual friend James Haslam. They eventually bought a crazy and charming dilapidated farmhouse together up in the Catskills, and I spent a lot of time with him there. I knew of his work, but the relationship didn’t really have a lot to do with that at first. David was unlike anyone I had ever met. Literary and refined, cultured—but he could easily be mistaken for a hobo. His humor was dark and homosexual. You were always laughing with him. It was very easy to be seduced by him. To me, he seemed like he was from another time.

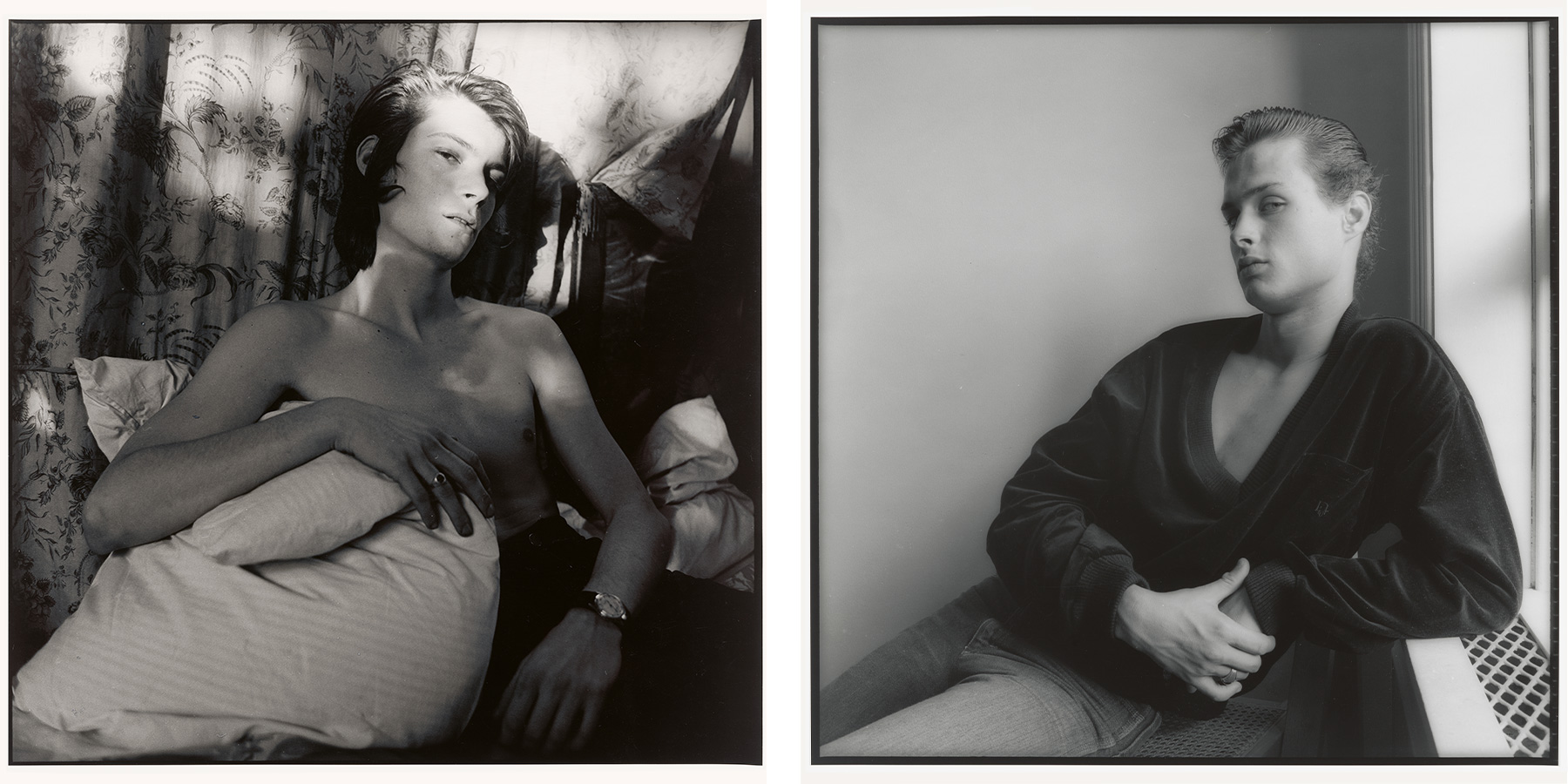

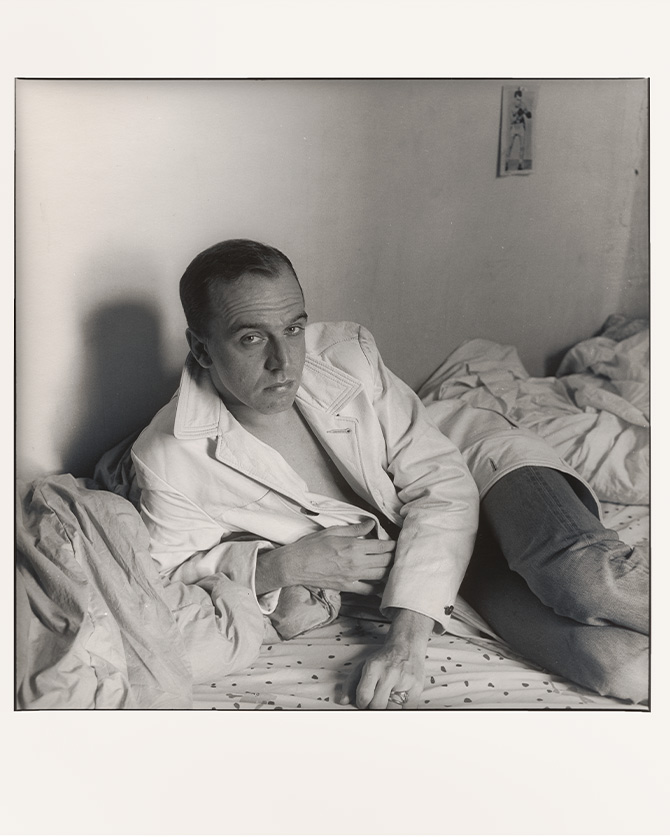

Sharon at Peter's, Cambridge, 1984

BAUMANN: I was trying to look at David’s work in the context of American photography. Many people mentioned Peter Hujar to me, because some of David’s pictures reminded them of Hujar’s. Hujar was about ten years older and died in 1987 at the age of 54. Did they know each other?

LOVE: From what I know, they didn’t. They were in a show together that Nan Goldin curated called “Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing” in winter 1989–90 at Artists Space in New York. It included many of David’s friends like Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Mark Morrisroe, Tabboo!, Shellburne Thurber, David Wojnarowicz, the painter Jane Dickson, and the writer Cookie Mueller. It was the first major exhibition on the subject of AIDS and let to a big controversy over government support of the arts.

BAUMANN: In an interview in 2002, David names Hujar as one influence, along with Julia Margaret Cameron, August Sander, Diane Arbus, pornography (specifically the magazine BLACK INCHES), classical painting, and obviously Nan Goldin and his friends from what is now called the Boston School of photography. People seem to suggest that they find Armstrong’s photography similar to Hujar’s.

GUYTON: I was reading a conversation between David and Jack Pierson and they discuss Hujar and Robert Mapplethorpe—who David said invited him to be in an exhibition at the Grey Art Gallery. David clearly preferred Hujar’s work—he says it was “earth-shattering” when he first saw it, and refers specifically to its authenticity and restraint, its proportions and “subdued grandeur.” He likens it to classical art. Mapplethorpe he found cold—more surface-oriented. Which I personally love about Mapplethorpe. But David obviously leaned more towards the classical. I can see his attraction to the subtlety of Hujar and the desire to have the subject—not only the photographer—play a part in the expression of the photograph. It happens in his own work. This restraint is interesting to me. I wish I had spoken to him about technical things. He and Hujar used light differently—I find a sharpness in Hujar’s photographs that isn’t in David’s. Obviously, David is slowly de-focusing over the years—to the blurry landscapes—but even in the portraits of the 80s and 90s, the images are softer. I wonder if this was technical: something to do with the different lenses they were using, or to do with different darkroom processes. As for Hujar having “done it already,” I find this to be something people say when they have a limited capacity for nuance, and a desire not to have to think about more than a very short list of artists. One can prefer Hujar to David, but that’s something else. They are both, like Nan—and like other more commercial photographers like Marcus Leatherdale, Edo Bertoglio, and Kate Simon, and probably many others—documenting downtown New York in this time period.

BAUMANN: I asked the critic and curator Martin Jaeggi, who worked with David, about Hujar and him. He said that one significant difference is the light. David avoided artificial light, used almost no flash, did almost no studio photography, preferring instead natural light, which “sculpted” people—and especially their faces. In 1992, during his stay in Berlin and with a 35mm camera, David started photographing landscapes. It seems at a great distance, quite literally, to his 20 years of portraiture photography. These photos are out of focus, and deal with a very different type of subject: landscapes and buildings. Do you know why he began on this series, Lisa?

LOVE: In his book ALL DAY EVERYDAY (2003) he explains why and when he started taking landscapes: “The first pictures I did of places was in Manhattan. They were in sharp focus. They were also pretty ghastly. I could have found better postcards. I realised I was more interested in recording my response to a place rather than a strict photographic document of it.” And then he went to Berlin and began shooting landscapes and palacescapes. I think he was really returning to painting with his camera. The light, the color, the blurred reality —it fit his personality. Otherworldly!

BAUMANN: He wanted to find out if he could make pictures without people. He felt it was a process of loosening up. Some of his friends told me that Armstrong hated working in fashion, that he would often send out caustic emails, and that, at the end of his life, he asked them to be published once he was gone.

LOVE: I don’t know about that. I’d say he approached his fashion photos with the same stillness and intimacy of all his pictures. Maybe he didn’t like dumbing himself down, working beneath his sense of beauty. He may or may not have loved fashion photography, but he certainly loved clothes. He would always call me before I went to an event: “What are you going to wear to the Gala?”

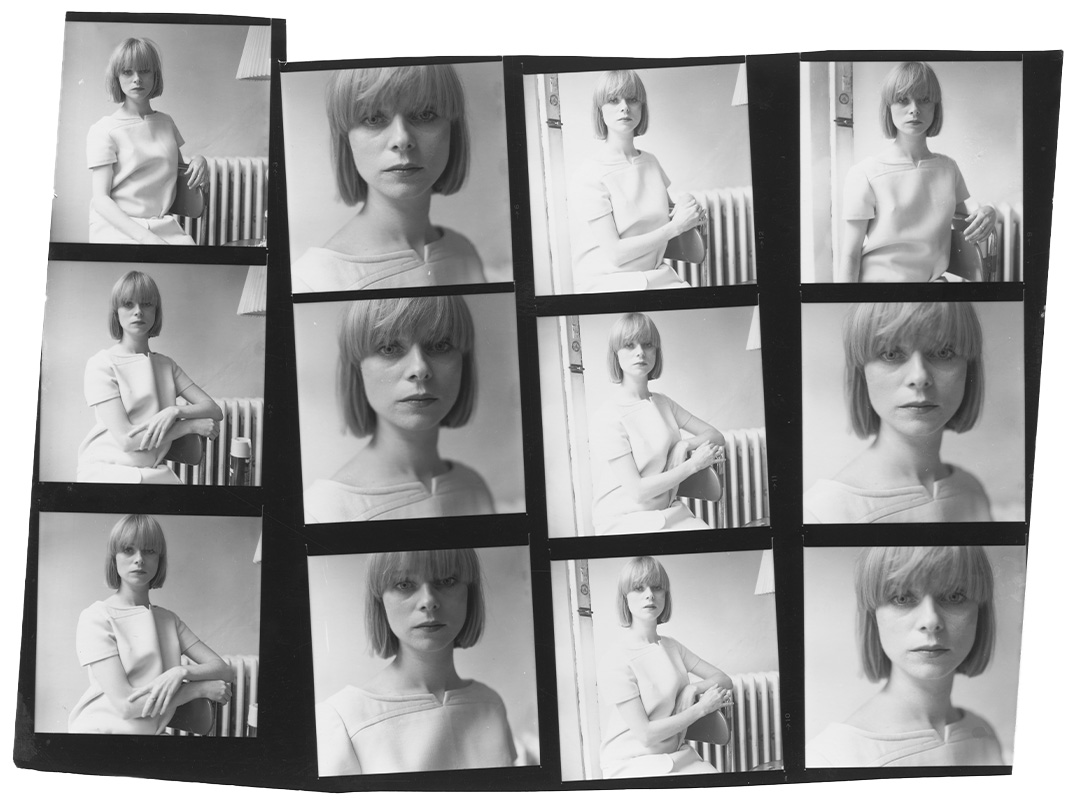

Rise in Her Chair, New York City, 1983